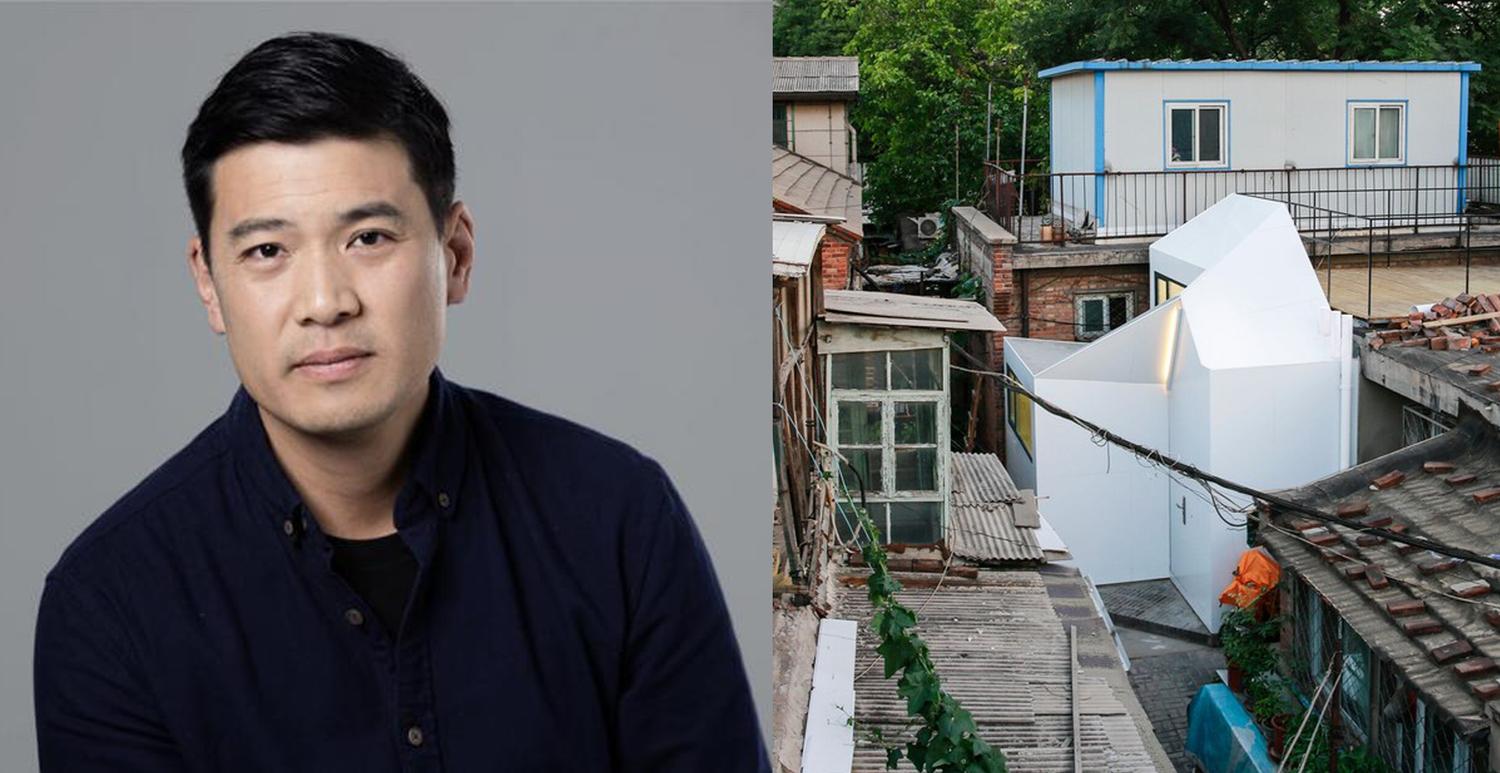

In Conversation with James Shen

- People’s Architecture Office (PAO)

by Hao Wang

Originally published on McGill Architecture Student Association

In the summer of 2018, I had the opportunity of doing a 12-weeks internship at People’s Architecture Office in Beijing. The office was undergoing an interesting transitional period while I was working there, where they were transitioning to designing large-scale projects. However, what interested me were their smaller scale, urban intervention projects. Curious about their approach to architectural design, I interviewed one of the founders of PAO, James Shen, at the end of my internship.

Hao Wang: You went to school for industrial design major for your undergraduate degree and architecture for your graduate degree. Why did you choose to switch majors and what are the differences between these two disciplines from your experience?

James Shen: I loved my undergraduate education. I worked as a product designer for a few years in the US and had really enjoyed that. We developed materials, mechanisms, and we had a workshop in the back with just the 3 of us. However, I think my (undergraduate) education lacked a theoretical base and it didn't have this internal criticism with prevails in architecture education. I wouldn't call it architecture versus product design; rather, I would call it a different spectrum of design. Product design is also mass-produced, whereas architecture is more customized, location specific. That is what I'm interested in, the social and political implications of architectural design.

HW: Why did you decide to start a firm with your two partners, Zang Feng and He Zhe?

JS: We were all working at FCJZ at the same time. They were the ones that came to me and suggested opening an office. We had never worked together as three people at FCJZ, and that was something we just took a chance.

The idea of opening an office is definitely attractive to people that you can do your own thing. For us, we were looking around at that time that a lot of architecture has lost its way. The design that was coming out didn't have to do with the people using these buildings and these spaces. We thought people were no longer the centre of the architecture.

It also has to do with the environment. If you look at it, the world of architecture historically has suffered from the effects of globalization and capitalism. My education, especially in my generation, was not based on this kind of world; it was based on a different world. A lot of projects we were studying were government projects. The public would be a very strong component along these projects. Today, things are different. We wanted to start a practice with people as the core of our thinking. There are a lot of differences between us and opportunities for exchange that would also help us create an identity that is particular to these kinds of thinking.

We wanted to emphasize collaboration and partnership, so we didn't want to call ourselves SOM or KPM or something like that. In our name, it represents a lot of our ideas especially the Chinese character “众” (Zhong).

HW: Do you think architects have the responsibility to influence city planner’s choices?

JS: Absolutely. Not only that, just saying that we have a role and we should have a place in the discussion is not really useful, we have to find a way to do that. To first understand why are we not in the discussion and then how do we create this position. However, I don't think this is always the case. There are many examples historically where architects are very much a part of the discussion with politics and planning. Beijing was formed by architects, the way that Tiananmen square was planned was with architects, it's very much a part of the identity of the country for that level.

HW: However, the new Beijing, after the WWII, was not planned by architects.

JS: I think it is. Those buildings built around Tiananmen square during the Mao period were built by the national architects for the government. That's a part of the history for contemporary architecture. I think we can refer to the past to understand the role of architects with these issues. If you look at it from a more practical point of view, if we take a stance where we only take decisions that stay within the boundaries that are given us, there's a lost opportunity where you actually are building these projects you see a lot of things going on the ground and you're also trying things out.

There are opportunities in this form that can also inform the planners and policymakers. They have to make decisions somehow. How do they make those decisions? By projecting the future and projecting possibilities. That's the main question we need to ask, how do these people make decisions, and can architects help make these decisions?

HW: A lot of projects People’s Architecture Office is doing are not strictly within the policy as far as I understand. Is it challenging to negotiate or have you influenced the policy in some ways?

JS: In terms of our idea, we do feel very strongly that we have a role and we've demonstrated that and the government also understands that. For example, Dashilar is a pilot demonstration area where the regulations are different from other places. This is one of the first places to experiment with a type of policy that has to do with how people can sell the property. It's called “自愿腾腿”, which means that these courtyard houses that are all subdivided. Where you have one courtyard houses that are occupied by several families, if you want to upgrade the courtyard house, you have to deal with all the families.

With the policy, any person can sell their house if they want to sell the house to the government, and they don't have to be in agreement with everyone. It creates these scattered vacant spaces all around the neighbourhood that the government still doesn't have a way to upgrade them. That's what gives us an opportunity to not torn down these buildings but still upgrade at the same time. It's a good example where there is a policy but doesn't have all the tools to do it. They also didn't know they could build something inside of an old house and they also didn't think there's a material you could use to do it until we worked it and understood in issues in details and started to deal with locals.

It would be hard to come up with a policy to deal with this issue if you didn't have ideas and didn't try things out and didn't have this pilot area. The government needs this kind of help. The government is still people that they are trying to deal with the same issues, and they might not have the solution but that doesn't mean they don't recognize the issue. I don't think any government official would say tearing down all these areas, relocating all these people, creating this kind of disruption would be the best way to do things. When you're In a situation like that, can we come in and say, maybe there's another way. That's a part of the way we can engage.

When we built the first plugin house it was a very small thing, for us it was a huge effort. A few months later, the mayor of Beijing went and visited this project. The access (to the government) is quite difficult, but with this project, you can access people that are quite high up. These are the people that are making these decisions that can influence the whole city.

Whether if this will lead to a definite policy change, we don't know when or if. But if our work continues, we believe more people will do it more so it is a long term process. Last year we did more pilot in Shenzhen using the system in a similar way dealing with the same issue. These are also government sponsored. And through these works with hutong area or urban villages, this might be a long term thing but we are also demonstrating an ability that can use for projects that are more immediate to the government.

I don't think architects provide solutions, but we're creating space for possibilities. Imagine ourselves are very separate from that process and say okay all of these are already set and were just coming in to do something that kind of look nice, I don't think this is what we want to do. I don't think it is making things any better.

HW: A lot of the earlier practices you were doing concern with the intervention of Beijing Hutong. They improve the inhabitant’s living conditions but also preserve the chaotic context at the same time. I recently just read an article called “Smooth City is the New Urban”, do you think the disappearance of spontaneous architecture is an inevitable path that a city needs to embark through development?

JS: I think the perspective of coming from the states and working here I can definitely compare places that are very regulated and places that are not regulated. A lot of people say the states are overly regulated, so many regulations that make it difficult to solve problems whereas the regulations are supposed to solve problems.

Right now, I have a position in Harvard Joint Centre for Housing. There is thinktank to create policy recommendations. I think people are trying to understand overregulation is an issue, its a concern. Also, on the other hand, being overly unregulated can also be a problem.

A lot of our works are inspired by informal activities that you see in China. Hutong as an example that you see a lot of people built additions they will subdivide, change their environment according to their needs, but sometimes they are done in a manner that can cause hazardous and social conflicts. Public safety is part of the government regulations, you don't want to have so much density that causes a health hazard, and what do you do with sanitation. But if it's so regulated that people are split up from each other and you don't have a society where people interact that can also cause social issues. There is a space for regulations that are open enough, there is space for people to participate in solving those problems. Informality that you see in urban villages, if that can work in a well thought out framework, then maybe you can have both without so much concern.

The People's canopy, as an urban intervention, is a tool for cities to test things out in different locations, and the public participates in this. You can imagine this moves from one location to another and volunteers can arrange it in certain ways with a program that the city wants to try. In this neighbourhood, they are missing a library. Instead of speculating it and putting a lot of hope into an idea that may happen, you can actually try it out and people can participate in it. It has been used in five or six cities, and have never been used in the same way. This actually is inspired by a lot of restraints in China where they would build this kind of canopy in front to extend the space. They make more money this way but also extend the restaurant into the street life. It borrows space from different times of the day where they would extend out when the officials are off work. We were inspired by how people use the city with certain tools. That's the thing I think it's interesting that is embodied in the society in a certain area but can also connect to places elsewhere.

HW: What type of public intervention are you more interested in?

JS: I'm interested in the conversation with the government and the community. I'm interested in us being able to support. It doesn't have to be a particular type of building.

HW: Do you have any advice for architecture students?

JS: To stay open-minded. Architecture is something that is continually being redefined. I don't think any one idea would inform if you are an architect or not. You can define yourself. Practical experiences are important. Practical meaning working very close to what would come out in the real world, to understand the materials, and understand the people that will be affected by what you're doing. Also, those policies that define the framework of what you're doing, to understand why the policy is made.